Introduction to Modeling (Part 1, Basics)

Today's livecode is here.

What's a Model?

Models

A model is a representation of a system that faithfully includes some but not all of the system's complexity. There are many different ways to model a system, all of which have different advantages and disadvantages. Think about what a car company does before it produces a new car design. Among other things, it creates multiple models. E.g.,

- it models the car in some computer-aided design tool; and then

- creates a physical model of the car, perhaps with clay, for testing in wind tunnels etc.

There may be many different models of a system, all of them focused on something different. As the statisticians say, "all models are wrong, but some models are useful". Learning how to model a system is a key skill for engineers, not just within "formal methods". Abstraction is one of the key tools in Computer Science, and modeling lies at the heart of abstraction.

In this course, the models we build aren't inert; we have tools that we can use the explore and analyze them!

Don't Be Afraid of Imperfect Representations

We don't need to fully model a system to be able to make useful inferences. We can simplify, omit, and abstract concepts/attributes to make models that approximate the system while preserving the fundamentals that we're interested in.

EXERCISE: If you've studied physics, there's a great example of this in statics and dynamics. Suppose I drop a coin from the top of the science library, and ask you what its velocity will be when it hits the ground. Using the methods you learn in beginning physics, what's something you usefully disregard?

Think, then click!

Air resistance! Friction! We can still get a reasonable approximation for many problems without needing to include that. (And advanced physics adds even more factors that aren't worth considering at this scale.) The model without friction is often enough.

Tools, Documentation, and Supplemental Reading

We'll be using the Forge declarative modeling language for this course. Forge is a "lightweight" modeling tool. Lightweight techniques tend to eschew full formalization and embrace some partiality (see Jackson and Wing) in exchange for cost-effectiveness, agility, and other benefits. As Bornholt, et al. write in their recent paper, a lightweight approach "do(es) not aim to achieve full formal verification, but instead emphasize(s) automation, usability, and the ability to continually ensure correctness as both software and its specification evolve over time."

This week will be a sort of "whirlwind tour" of Forge. We'll cover more in future classes; you can also access the Forge documentation.

Forge Updates

We'll be updating Forge regularly; expect an update roughly every week. Sometimes we may update more often to resolve issues, etc. or less often if no changes are needed. Updates will be announced on EdStem, and each update will have a new version number. Please keep Forge updated and include your version number in questions or bug reports.

There will be a Forge update coming this week by Wednesday morning, before class; you'll use Forge for the first time in this week's lab.

Systems vs. Models (and Implementations)

When we say "systems" in this module, we mean the term broadly. A distributed system (like replication in MongoDB) is a system, but so are user interfaces and hardware devices like CPUs and insulin pumps. Git is a system for version control. The web stack, cryptographic protocols, chemical reactions, the rules of sports and games---these are all systems too!

To help build intuition, let's work with a simple system: the game of tic-tac-toe (also called noughts and crosses). There are many implementations of this game, including this one that Tim wrote for these notes in Python. And, of course, these implementations often have corresponding test suites, like this (incomplete) example.

Exercise: Play a quick game of tic-tac-toe. If you can, find a partner, but if not play by yourself.

Notice what just happened. You played the game, and so doing ran your own "implementation" of the rules. The result you got was one of many possible games, each with its own specific sequence of legal moves, leading to a particular ending state. Maybe someone won, or maybe the game was a tie. Either way, many different games could have ended with that same board.

Declarative modeling is different from programming. When you're programming traditionally, you give the computer a set of instructions and it follows them. This is true whether you're programming functionally or imperatively, with or without objects, etc. Declarative modeling languages like Forge work differently. The goal of a model isn't to run instructions, but rather to describe the rules that govern systems.

Here's a useful comparison to help reinforce the difference (with thanks to Daniel Jackson):

- An empty program does nothing.

- An empty model allows every behavior.

Modeling Tic-Tac-Toe Boards

What are the essential concepts in a game of tic-tac-toe?

Think, then click!

We might list:

- the players

XandO; - the 3-by-3 game board, where players can put their marks;

- the idea of whose turn it is at any given time; and

- the idea of who has won the game at any given time.

Let's start writing our model in Forge! We certainly need a way to talk about the noughts and crosses themselves:

#lang forge/bsl

abstract sig Player {}

one sig X, O extends Player {}

The first line of any Forge model will be a #lang line, which says which sub-language the file is. We'll start with the Froglet language (forge/bsl, where bsl is short for "beginner student language") for now. Everything you learn in this language will apply in other Forge languages, so I'll use "Forge" interchangeably.

You can think of sig in Forge as declaring a kind of object. A sig can extend another, in which case we say that it is a child of its parent, and child sigs cannot overlap. When a sig is abstract, any member must also be a member of one of that sig's children; in this case, any Player must either be X or O. Finally, a one sig has exactly one member---there's only a single X and O in our model.

We also need a way to represent the game board. We have a few options here: we could create an Index sig, and encode an ordering on those (something like "column A, then column B, then column C"). Another is to use Forge's integer support. Both solutions have their pros and cons. Let's use integers, in part to get some practice with them.

abstract sig Player {}

one sig X, O extends Player {}

sig Board {

board: pfunc Int -> Int -> Player

}

Every Board object contains a board field describing the moves made so far. This field is a partial function, or dictionary, for every Board that maps each (Int, Int) pair to at most one Player.

What Is A Well-Formed Board?

These definitions sketch the overall shape of a board: players, marks on the board, and so on. But not all boards that fit this definition will be valid. For example:

- Forge integers aren't true mathematical integers, but are bounded by a bitwidth we give whenever we run the tool. So we need to be careful here. We want a classical 3-by-3 board with indexes of

0,1, and2, not a board where (e.g.) row-5, column-1is a valid location.

We'll call these well-formedness constraints. They aren't innately enforced by our sig declarations, but often we'll want to assume they hold (or at least check that they do). Let's encode these in a wellformedness predicate:

-- a Board is well-formed if and only if:

pred wellformed[b: Board] {

-- row and column numbers used are between 0 and 2, inclusive

all row, col: Int | {

(row < 0 or row > 2 or col < 0 or col > 2)

implies no b.board[row][col]

}

}

This predicate is true of any Board if and only if the above 2 constraints are satisfied. Let's break down the syntax:

- Constraints can quantify over a domain. E.g.,

all row, col: Int | ...says that for any pair of integers (up to the given bidwidth), the following condition (...) must hold. Forge also supports, e.g., existential quantification (some), but we don't need that here. We also have access to standard boolean operators likeor,implies, etc. - Formulas in Forge always evaluate to a boolean; expressions evaluate to sets. For example,

- the expression

b.board[row][col]evaluates to thePlayer(if any) with a mark at location (row,col) in boardb; but - the formula

no b.board[row][col]is true if and only if there is no such `Player``.

- the expression

Well talk more about all of this over the next couple of weeks. For now, just keep the formula vs. expression distinction in mind when working with Forge.

Notice that, rather than describing a process that produces a well-formed board, or even instructions to check well-formedness, we've just given a declarative description of what's necessary and sufficient for a board to be well-formed. If we'd left the predicate body empty, any board would be considered well-formed---there'd be no formulas to enforce!

Running Forge

The run command tells Forge to search for an instance satisfying the given constraints:

run { some b: Board | wellformed[b]}

When we click the play button (or type racket <filename> in the terminal), the engine solves the constraints and produces a satisfying instance, (Because of differences across solver versions, hardware, etc., it's possible you'll see a different instance than the one shown here.) A browser window should pop up with a visualization.

If you're running on Windows, the Windows-native cmd and PowerShell will not properly run Forge. Instead, we suggest using one of many other options: the VSCode extension, DrRacket, Git bash, Windows Subsystem for Linux, or Cygwin.

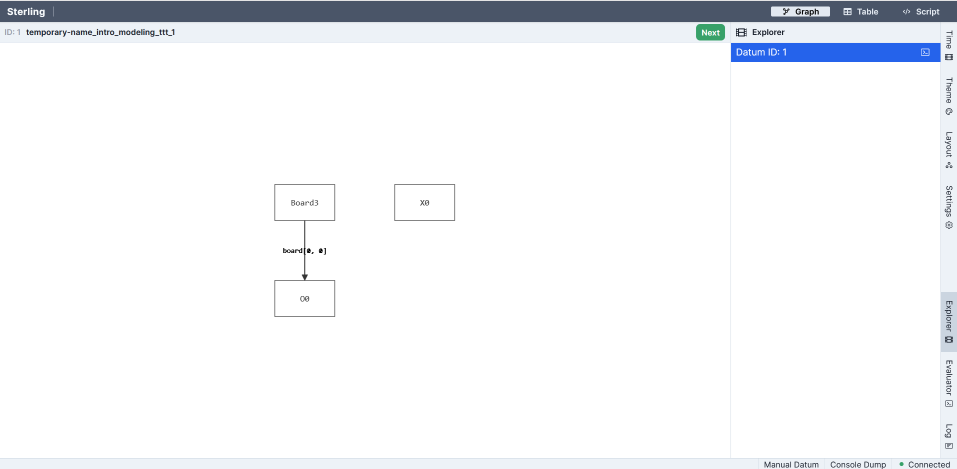

There are many options for visualization. The default which loads initially is a directed-graph based one:

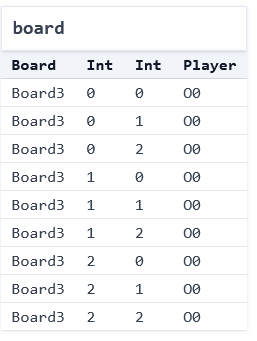

For now, we'll use the "Table" visualization---which isn't ideal either, but we'll improve on it next time.

This instance contains a single board, and it has 9 entries. Player O has moved in all of them (the 0 suffix of O0 in the display is an artifact of how Forge's engine works; ignore it for now). It's worth noticing two things:

- This board doesn't look quite right: player

Ooccupies all the squares. We might ask: has playerObeen cheating? But the fact is that this board satisfies the constraints we have written so far. Forge produces it simply because our model isn't yet restrictive enough, and for no other reason. "Cheating" doesn't exist yet. - We didn't say how to find that instance. We just said what we wanted, and the tool performed some kind of search to find it. So far the objects are simple, and the constraints basic, but hopefully the power of the idea is coming into focus.

Testing Our Predicate

The predicate we just wrote is essentially a function that returns true or false for whichever instance we're in. Thus, we can write tests for it the same way we would for any other boolean-valued function, by writing examples:

-- Helper to make examples about a single predicate

pred all_wellformed { all b: Board | wellformed[b]}

-- suite to help group tests

-- all_wellformed should be _true_ for the following instance

example firstRowX_wellformed is {all_wellformed} for {

Board = `Board0

X = `X O = `O

Player = X + O

`Board0.board = (0, 0) -> `X +

(0, 1) -> `X +

(0, 2) -> `X

}

-- all_wellformed should be _false_ for the following instance

example off_board_not_wellformed is {not all_wellformed} for {

Board = `Board0

X = `X O = `O

Player = X + O

`Board0.board = (-1, 0) -> `X +

(0, 1) -> `X +

(0, 2) -> `X

}

Notice that we've got a test thats a positive example and another test that's a negative example. We want to make sure to exercise both cases, or else "always true" or "always" false could pass our suite.

We'll talk more about testing soon, but for now be aware that writing some examples for your predicates can help you avoid bugs later on.

Forge has some syntax that can help reduce the verbosity of examples like this, but we'll cover it later on.

Reflection: Implementation vs. Model

So far we've just modeled boards, not full games. But we can still contrast our work here against the implementation of tic-tac-toe shared above. We might ask:

- How do the data-structure choices, and type declarations, in the implementation compare with the model?

- Is there an "implementation" that matches what we just did? (The program's purpose isn't to generate boards, but to play games.)

Next time, we'll extend our model to support moves between boards, and then use that to generate and reason about full games.